Domain DNS Access: What Marketers Need and What They Don’t

02/17/2026

Client onboarding often stalls on a single question: “Can you send us DNS access?” For many clients, that request feels like handing over the keys to the building, even if your real goal is only to verify a domain or connect tracking.

The good news is that most marketing work requires a very small slice of DNS changes, and in many cases you do not need a DNS login at all. What you need is a clean, precise DNS change request, the right owner on the client side, and a quick verification step.

DNS access, registrar access, hosting access: stop mixing them up

Marketers (and clients) often use “domain access” as a catch-all term. In practice, there are three different control planes:

- Registrar (where the domain is registered): controls domain ownership, transfers, and often who can manage DNS.

- DNS provider (where records live): could be the registrar, Cloudflare, AWS Route 53, Google Cloud DNS, etc.

- Hosting / CMS (where the website runs): Webflow, WordPress, Shopify, custom hosting, etc.

If your request is “DNS access,” you are asking for the middle layer only. That is already sensitive, but it is not the same as asking for website admin access or registrar ownership.

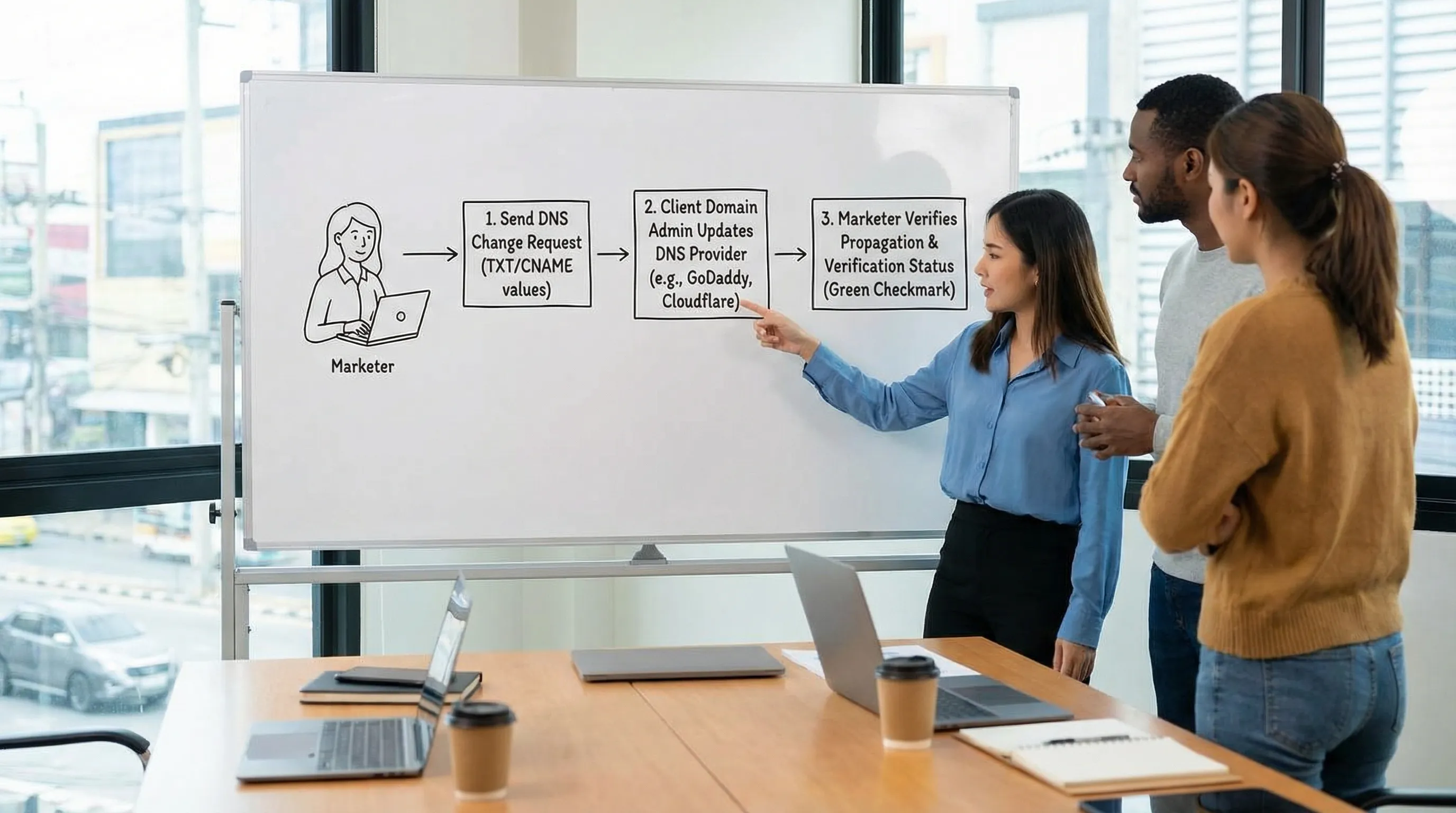

The principle that keeps everyone safe: ask for a record change, not a login

When you request full DNS access “just in case,” you create real risk:

- One accidental edit can take down email, the website, or production apps.

- Clients lose auditability, because the change is no longer tied to their internal IT process.

- It increases the chance you are blamed for unrelated outages.

A better operational rule for agencies is:

Default to client-owned DNS, client-executed DNS changes, and agency-provided exact record instructions.

If you do need direct access, ask for limited DNS-editor permissions, not registrar ownership or full admin.

What marketers actually need DNS for (the 5 common cases)

Most marketing-related DNS work falls into a small set of patterns. If you can name the pattern, you can request the minimum required change.

1) Domain verification (SEO and ad platforms)

Verification proves you control a domain. The most common method is a TXT record.

Typical examples:

- Google Search Console domain property verification uses a DNS TXT record (Google documentation).

- Meta Business domain verification commonly uses a TXT record (Meta documentation).

What you need: A one-time TXT record added. Often no ongoing DNS access.

What you do not need: Nameserver changes, registrar transfer access, or website admin access.

2) First-party tracking and attribution (CNAME records)

Many tools support a first-party tracking setup using a CNAME record (for example, mapping a subdomain like track.yourdomain.com to a vendor endpoint). The marketing goal is usually better attribution resilience, cleaner cookie behavior, or less ad-blocker interference.

What you need: A CNAME record on a subdomain, sometimes plus a TXT record.

What you do not need: Editing the root A record (@) unless you are actually moving the website.

3) Email authentication for newsletters and lifecycle email (SPF, DKIM, DMARC)

If you send email from the client’s domain (newsletters, lead nurturing, transactional notifications), DNS is part of deliverability and brand protection.

- SPF is usually a TXT record.

- DKIM is commonly a CNAME or TXT record.

- DMARC is a TXT record.

This can apply to email platforms and also to CRMs that send email on your behalf. If a client uses a CRM for outbound or notifications (for example Dr. CRM), email authentication is one of the first things to get right to reduce spam placement and spoofing risk.

What you need: A small set of TXT/CNAME records, plus alignment with whoever owns the sending domain.

What you do not need: Changing MX records unless the client is intentionally migrating mailbox providers.

4) Subdomains for landing pages, microsites, or regional sites

Common scenarios:

lp.client.comfor landing pagesgo.client.comfor a campaign hubeu.client.comfor regional content

This can require a CNAME (common with SaaS landing page tools) or A/AAAA records (more common with custom infrastructure).

What you need: A subdomain added with the vendor’s specified record.

What you do not need: Full access to the entire zone if the client can add the one record for you.

5) Redirect-adjacent misunderstandings (what DNS cannot do)

A frequent onboarding failure mode is asking for DNS changes to “set up redirects.” DNS does not create URL path redirects (like /pricing to /plans). Redirects are handled at the web server, CDN, or application layer.

DNS can only route hostnames (like www.client.com) to targets, it does not understand paths.

What you need instead: Access to the hosting/CDN layer, or a request to the web team.

The DNS changes marketers should avoid requesting (unless you truly own the migration)

These changes are high-risk and usually belong to IT, engineering, or a designated domain administrator:

- Nameserver (NS) changes: switching DNS providers is effectively moving the entire DNS zone.

- Registrar transfer / ownership changes: this is legal ownership territory.

- Root (

@) A/AAAA record changes: can take the website down if mishandled. - Deleting or “cleaning up” old records: seemingly unused records often back critical systems.

- MX record changes: can break inbound email company-wide.

- DNSSEC changes: security-sensitive, can cause resolution failures if misconfigured.

If your campaign depends on any of the above, treat it as a coordinated technical change with rollback plans.

Quick mapping: marketing tasks to DNS records (and who should own it)

Use this table to align expectations in kickoff and avoid over-requesting access.

| Marketing goal | Typical DNS record(s) | Change frequency | Risk level | Best owner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verify domain for ad/SEO tools | TXT | One-time | Low | Client admin executes from your instructions |

| First-party tracking subdomain | CNAME (sometimes TXT) | Rare | Medium | Client admin or IT |

| Email authentication (deliverability) | TXT, CNAME | Rare, but important | Medium | IT or whoever owns email |

| Landing page subdomain | CNAME or A/AAAA | Occasional | Medium | Web/IT |

| Migrate DNS provider | NS, full zone | Project-based | High | IT/engineering |

| Move website hosting | A/AAAA, CNAME, sometimes TXT | Project-based | High | Web/engineering |

The minimum “DNS access” an agency should ask for

When direct access is required, avoid asking for “admin.” Instead, specify the least-privilege role that still lets the work happen.

| Permission level | What it usually allows | When it is appropriate for marketers |

|---|---|---|

| Read-only | View records and history | Debugging, audits, preparing precise change requests |

| DNS editor (zone-level) | Add/edit records (TXT, CNAME, A, etc.) | Only if client cannot execute changes quickly and you have a controlled process |

| Admin / account owner | Manage users, zones, billing, transfers | Almost never appropriate for an agency |

If the client’s DNS provider cannot do granular roles well, default back to “client executes changes from agency instructions.”

The DNS Change Request Packet (copyable internal standard)

The fastest way to get DNS changes done (without back-and-forth) is to send a complete, unambiguous packet.

Include:

- DNS provider (where they should log in): “Cloudflare” vs “GoDaddy” matters.

- Zone:

client.com(and note if it is split across providers). - Record type: TXT, CNAME, A, etc.

- Name/Host:

@,www,_dmarc,track, etc. - Value/Target: the exact string (copy-paste safe).

- TTL: “Auto” is usually fine, or specify if the vendor requires a value.

- Purpose: “Verify domain for Meta Business,” “Enable DKIM,” etc.

- Deadline and rollout window: especially if email could be affected.

- Rollback instruction: “Remove this TXT record if verification fails,” or “Restore previous value.”

This turns “Can we get DNS access?” into “Please add this TXT record, then tell us when it’s live.”

Verification: how marketers confirm DNS changes without guesswork

DNS changes are not “done” when someone says they updated a record. You need a verification habit.

Know what “propagation” actually means

Most DNS changes become visible based on:

- TTL caching

- Resolver behavior

- Whether you are querying the authoritative nameservers

In practice, many TXT/CNAME changes show up quickly, but you should plan for delays.

Practical verification options

- Check inside the destination platform first (Search Console, Meta, your email provider) because it tells you whether the verification is accepted.

- Use a DNS lookup tool or CLI (

dig,nslookup) if you have it available. - If the platform requires it, confirm the record is on the correct host (for example,

_dmarc.client.comvsclient.com).

Tip: When verification fails, the most common causes are wrong host field, wrong zone (editing client.net instead of client.com), or adding the record at the registrar while DNS is hosted elsewhere.

A clean way to explain DNS to non-technical clients (without sounding scary)

Clients hesitate because DNS feels like “production infrastructure,” and they are right. A simple explanation you can use:

“DNS is the public address book for your domain. We typically only need to add one verification record (like a TXT record) so platforms can confirm you own the domain. You keep ownership, and we will send exact copy-paste instructions.”

This reduces anxiety and speeds approval.

Operationalizing DNS in client onboarding (so it stops being a blocker)

DNS is rarely the only access dependency. The real issue is that onboarding spans multiple platforms and multiple owners (marketing, IT, finance, legal). The fix is to standardize the handoff.

A lightweight approach agencies use:

- Collect DNS context on Day 0: DNS provider, who can edit it, and who approves changes.

- Pre-write the DNS change packets for verification, tracking, and email auth.

- Run a 15-minute verification sprint as soon as the client confirms changes.

If you want this to be repeatable across clients, tools like Connexify can help you turn “access chaos” into a single branded onboarding flow. Instead of scattered emails and screenshots, you can use one onboarding link to collect the DNS owner, route tasks to the right person, request only the minimum permissions, and keep the process consistent across platforms.

The bottom line

For marketers, “DNS access” should almost never mean “hand over the domain.” In most engagements, you only need one of these outcomes:

- A TXT record to verify the domain

- A CNAME for tracking or a subdomain

- A small set of TXT/CNAME records for email authentication

When you standardize the request (record, host, value, purpose, rollback) and keep changes client-owned by default, you get faster launches, fewer security objections, and far less risk for everyone involved.